All AI Models Make the Same Mediocre Creative Work // BRXND Dispatch vol 99

New research from Springboards shows humans can barely tell leading LLMs apart—and the models are training creativity out of themselves.

You’re getting this email as a subscriber to the BRXND Dispatch, a newsletter at the intersection of marketing and AI.

We interviewed Springboards.ai CEO Pip Bingemann about new research into why all the leading AI models produce the same mediocre creative work.

Springboards just wrapped a creativity benchmark study with nearly 700 marketing and advertising professionals evaluating 11,000+ pairwise comparisons across major LLMs. We chatted with co-founder Pip Bingemann to talk through what they found.

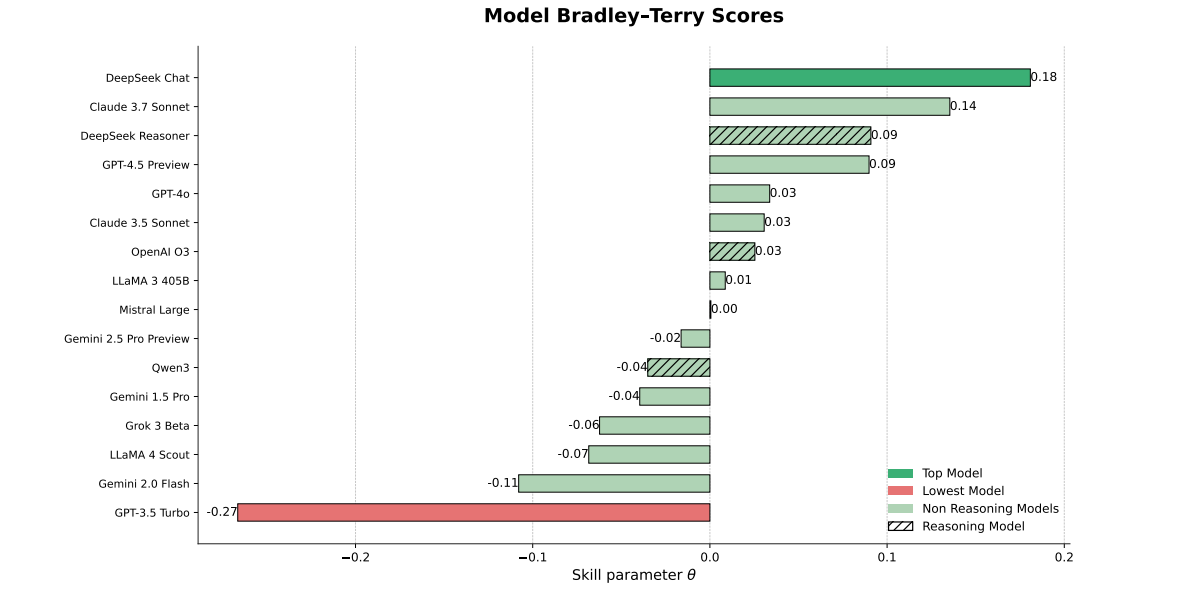

The biggest insight is that humans can’t really tell models apart when judging creative work. DeepSeek Chat technically won, but with win rates hovering around 50-55%, the real story isn’t which model came out on top—it’s that the entire field is clustered in a narrow band of mediocrity. “It’s like asking people who they think would win between two mid-table teams,” Bingemann explains. The top-rated model beats the lowest only about 61% of the time.

The Confidence Gap

Here’s where it gets interesting. Springboards ran the same evaluation with LLMs as judges, and the models were 5-10x more confident in their assessments than humans were.

o3 and DeepSeek Reasoner topped the LLM rankings—both reasoning models that strongly prefer outputs with clear logical progression. Humans, meanwhile, preferred DeepSeek Chat, which the AI judges ranked much lower. “Models prefer a very clear logic that they can follow from A to B,” Bingemann says. “They don’t want big creative leaps.”

LLMs like things that look rational and professionally structured. Humans are drawn to messier, more subjective work. The models vote with the certainty of a top contender beating a mid-table team, even when the actual creative output is indistinguishable.

This has implications beyond benchmarking. If these models increasingly mediate how we encounter ideas—whether through AI search, recommendation systems, or content moderation—we’re selecting for outputs that feel professionally written but lack genuine creative risk.

The Variation Problem

The study also measured output diversity using cosine similarity analysis. This is where things get genuinely disturbing. The models have near-zero variation in their creative outputs. They’re funneling everyone toward identical creative territory.

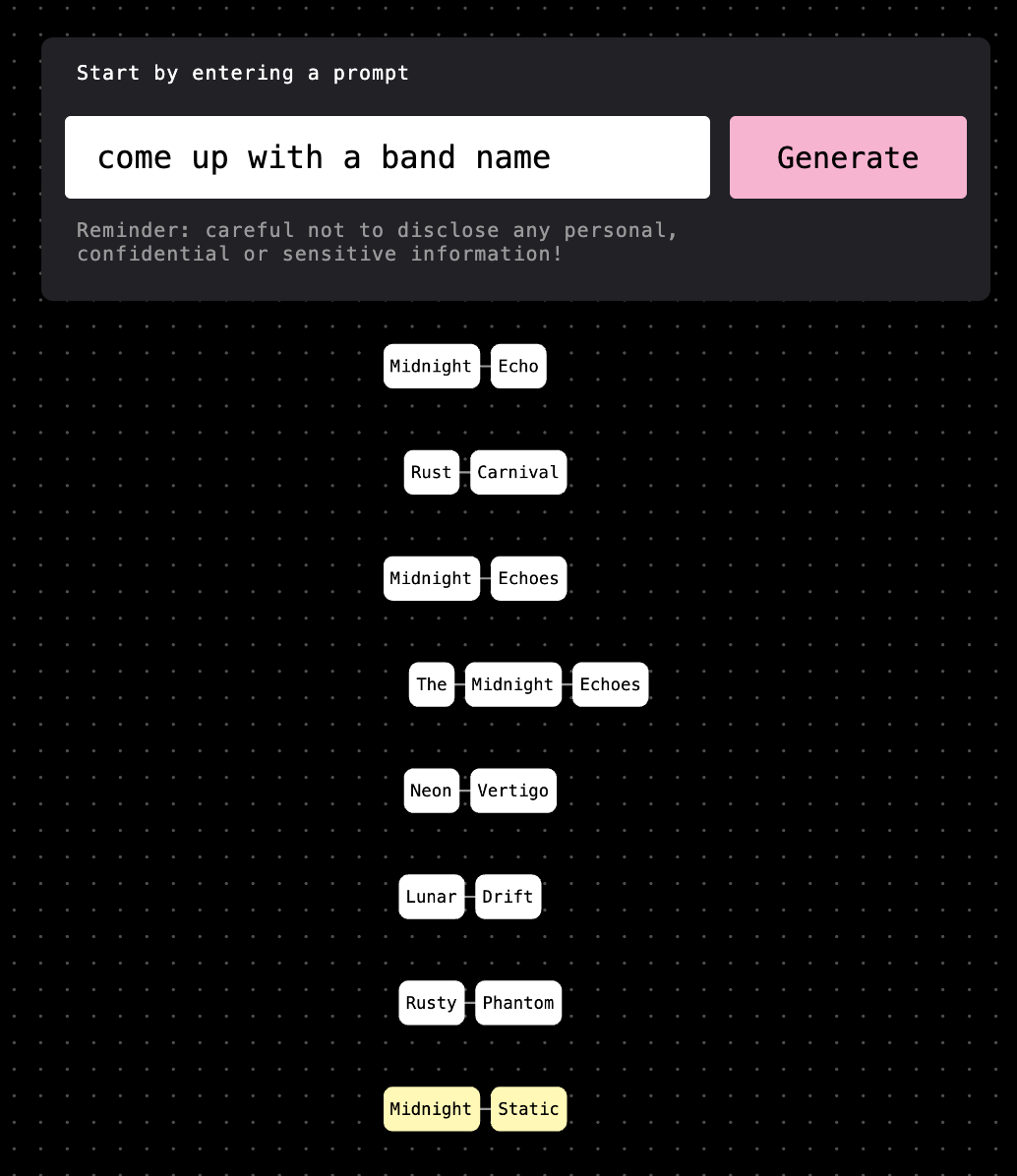

During our conversation, Bingemann pulled up Springboards’ Fork AI tool and demonstrated the problem live. He asked for a band name ten times. The results were pretty uneventful: Midnight Reverie, Midnight Mirage, Phantom Tide, Phantom Pulse—variations on the same handful of templates. “These models just do not have any variation in them whatsoever,” he says.

In the formal study, Gemini 2.5 Pro Preview and Claude 3.7 Sonnet showed the highest variation across prompt types. ChatGPT, currently the most widely used model for creative work, sits in the middle of the pack. And when Springboards tested older models like GPT-3.5, they found more variation than newer ones. We’re optimizing these systems for accuracy and consistency, and in the process, we’re training the creativity out of them.

“The benchmarks that get published are broken for the industry that advertising and marketing people are in,” Bingemann says. “All the tests are on things like maths, physics, doctors, PhD exams—benchmarks where there is a right and a wrong answer.”

Creativity doesn’t have right answers. It thrives on variation, on unexpected connections, on outputs that surprise us. But we’re training models on datasets that reward convergence to the mean. By the time you layer on RLHF to make these systems “helpful” and “appropriate,” you’ve systematically removed the capacity for genuine creative leaps.

This threatens to flatten culture at scale. We’re already seeing it: AI-generated music flooding streaming platforms, visual slop proliferating across social feeds, even UK Parliament speeches showing surges in AI-generated language patterns. But there’s another way to read this: maybe these models aren’t flattening culture so much as revealing how flat it already was. The templates, the clichés, the convergent thinking—that was already dominant. AI is just making it cheaper to produce and harder to ignore. The internet is becoming a closed loop where models train on increasingly model-generated content, but perhaps the loop was always tighter than we wanted to admit.

A Way Forward

Springboards isn’t saying abandon AI for creative work. They’re proposing something more pragmatic: use LLMs for volume, humans for selection. Their Fork AI experiment demonstrates this approach. It lets you interrupt a model’s generation at any word and fork it in a different direction—injecting human variation at the token level. You get the speed and scale of the model, but you break its tendency to converge on the same outputs everyone else is getting. “Because the models are not good at variation, we think the best way to actually drive variation is to inject human variation,” Bingemann says.

It’s a reasonable middle ground, though it still puts a lot of faith in humans recognizing good ideas when the entire point of creativity is that novel ideas often look wrong at first. But it’s better than letting the models run unsupervised toward the same mediocre middle.

Springboards will release monthly variation benchmarks starting early next year—tracking whether these models get more or less creative over time. Given what we’ve seen with GPT-3.5 having more variation than GPT-4, I wouldn’t bet on progress. The Creativity Benchmark is live now at experiments.springboards.ai. You can test which models match your creative preferences and see if you agree with the crowd.

The research makes one thing clear: creativity is the domain where humans still can’t agree on what’s good. And maybe that disagreement is exactly what makes human creativity valuable.

Try the benchmark: experiments.springboards.ai

Read the full paper: Creativity Benchmark on arXiv

And finally, watch Carolyn Murphy demo Springboards’ approach at BRXND:

If you have any questions, please be in touch. As always, thanks for reading.

Noah and Claire

I recently found the same when using a few different models to create abstract superhero names. The models gave me identical outputs in most cases, riffing in similar ways from known sets.